“Why do you stand here looking into the sky? This same Jesus, who has been taken from you into heaven, will come back in the same way you have seen him go into heaven.”

Acts 1:11

Somewhere along the line we appear to have misplaced the Second Coming. Relegated to the backwaters of contemporary theology or made dubious by a perpetual parade of pious prognosticators, the return of Christ has faded from our front-and-center Christian proclamations. It has become a mere footnote to the modern gospel, a fuzzy ancillary legend of minimal immediate import. The venerable threefold message of a savior who died, rose, and is returning seems to have dwindled into a binary cross and cope formula: Jesus forgives you, now do your best. The promised second coming is a lovely notion, but it seems to have little, if any, practical value for walking out the Christian life. For the daily grind, church cuisine tends to favor ground beef rather than pie in the sky.

This reflects the modern church’s shift of emphasis from the hereafter to the here and now expressed by a gospel that seems more salve than salvation. And set against today’s urgent physical and social needs, talk of a better someday seems a scant provision for surviving this day.

But the return of Jesus is not a glamorous accessory to his sacrifice and resurrection, nor is it a door prize for those with tickets to the main event or a carrot on a stick for some simpleton saints. Far from it. The second coming of Christ is, in fact, an essential part of the gospel and as necessary to confirm its legitimacy as is the resurrection itself.

First, without the second coming, Christianity is a fundamentally subjective experience that cannot verify universal truth. A person’s experience with Jesus, as real and life changing as that may be, only verifies that he or she has had an experience; it is a true experience but may not point to a greater truth. (Psychiatric wards are filled with authentic experiences that do not align with objective truth.) Granted, signs and wonders—including healing, deliverance, and other miracles—historically attest to the objective truthfulness of the gospel, but those phenomena are exceedingly rare these days. (There’s a good reason for this, but that’s another discussion.) Jesus and the New Testament writers point instead to love as the greatest evidence. To be sure, love is a powerful witness, but as Jesus declares, the believers’ love for each other testifies “that you are my disciples.” What love does not do is prove that Jesus is the son of God and savior of the world. There are, after all, any number of cults and clubs that can boast a robust fraternity, but that doesn’t mean that their charters define truth.

Jesus himself underscores the subjective nature of Christianity. “The coming of the kingdom of God is not something that can be observed, nor will people say, ‘Here it is,’ or ‘There it is,’ because the kingdom of God is within you [or in your midst].” In other words, the reality of the kingdom resides only within those who believe. That the greatest truth would be made known on such a limited scale troubled some of the disciples. “Lord,” asked one. “Why do you intend to show yourself to us and not to the world?” To which Jesus replied, “Those who love me will obey my teaching. My Father will love them, and we will come to them and make our home with them.” Objective proof of the gospel will have to wait until the return of its author when every eye will see him, even those who pierced him. When the Son returns, both faith and unbelief will succumb to objective fact; the kingdom of God will be within and without.

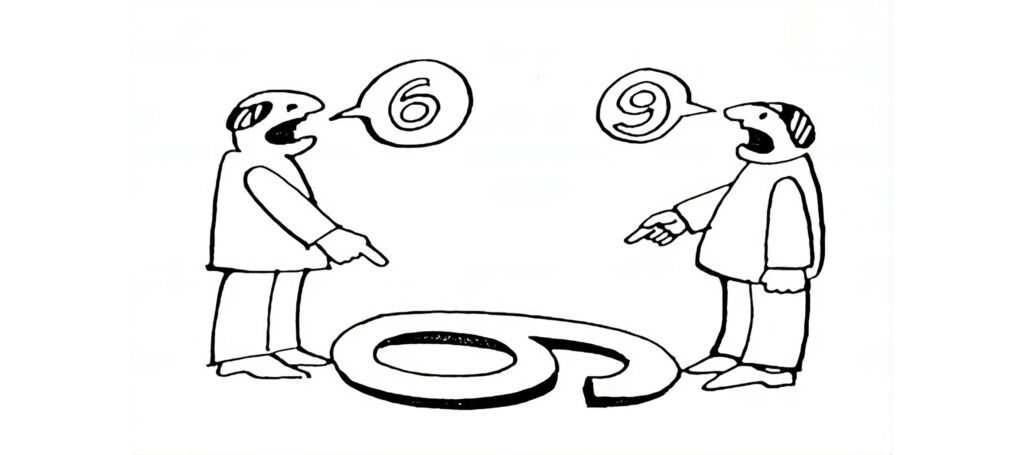

Second, because the kingdom of God is for now a fundamentally subjective experience (no matter its outward expression) until the Lord’s return, the gospel can be falsified. Arguments against the veracity of the gospel are as authoritative as the arguments defending its truthfulness. It’s one subjective experience versus another. This does not imply that there are two sets of facts. Facts are facts. Disputes nearly always arise from differing interpretations of the facts at hand. A good example is the disagreement about what the earth’s archeological data suggests. Both parties observe the same empirical evidence, but they strongly disagree about what that evidence is evidence of. In the same way, the claims and experiences of Christians can be countered by those with different claims and experiences. Muslims have their own holy book and spiritual encounters, as do Hindus and Buddhists. Even atheists can point to authoritative sources and appeal to personal experience—even if it’s the experience of the absence of spiritual experience.

Every honest witness is a reliable witness of his own experience, whatever it is. If a madman is convinced that he’s Napoleon and says so, he’s not lying. We may disagree, but that’s our viewpoint, not his. We can argue with him, but for the madman all evidence irrefutably points to his Napoleonic identity. T.S. Eliot asserted that everything can be shown to be true from some perspective. (Einstein might agree to a degree.) Our madman may entertain delusions, but they are real delusions. Until the return of Christ, it’s testimony versus testimony.

Peter warns of those who doubt that the Second Coming will happen at all: You must understand that in the last days scoffers will come . . .They will say, “Where is this ‘coming’ he promised? Ever since our ancestors died, everything goes on as it has since the beginning of creation.” Their perspective, Peter maintains, is based on willful ignorance, but Paul insist that this is the case for everybody. No matter; until Jesus returns, everything is debatable.

Finally, not only is the Second Coming the last, necessary confirmation of the gospel and the vindication of the church, it is also—and maybe mostly—a rescue operation. Without the return of Christ, the church would be destroyed. Talk of a triumphant church often omits the sobering reality that the victory will come after the defeat of the saints, a defeat so profound that only the return of the King will deliver them. In his Revelation, John speaks of a great Dragon who enthrones a terrifying beast and empowers him in order to subdue all who are in the world:

The beast was given a mouth to utter proud words and blasphemies and to exercise its authority for forty-two months. It opened its mouth to blaspheme God, and to slander his name and his dwelling place and those who live in heaven. It was given power to wage war against God’s holy people and to conquer them.

In the end, Jesus will come again for a besieged people who are faithfully awaiting deliverance. No amount of spiritual bravado will save them from the enemy. In the face of the full fury of hell, all the saints can do is remain steadfast. “You will be hated by everyone because of me,” Jesus warned his disciples, “but the one who stands firm to the end will be saved.” The church’s triumph is the return of the King.

The grand finale of the gospel is not the resurrection of Jesus; it is the promised Parousia. We shall not be fully saved until he comes again for us. He will rescue us from a world destined for destruction and gather us to himself forever. This is the great hope and should be unapologetically proclaimed alongside the message of the Cross and Resurrection. The second coming of Christ is a hope beyond cope, a glorious impetus to righteousness, perseverance, and zeal—and we need to hear more of it.

The hour has already come for you to wake up from your slumber, because our salvation is nearer now than when we first believed.