This we speak, not in words taught us by human wisdom but in words taught by the Spirit, expressing spiritual realities with spiritual words.

1 Corinthians 2:13

The stereotypical image of the Old Testament prophet is an indignant bludgeon of a man sporting wild hair, a beard, crazy eyes, and a ratty tunic who bellows denunciation and certain doom. He is a disrupter, an agent of agitation, an instrument of confrontation. He is possessed by divine fury and conscripted to expose the arrogance and apostasy of men. He is a clear channel for the Word of the Living God and, therefore, intolerable.

The New Testament prophet has been tamed. Since Jesus has perfectly revealed the Father and the Spirit has been poured out upon all believers, the prophet no longer holds his (or her) position as the privileged and exclusive mouthpiece of God. Unlike his Old Testament counterpart whose pronouncements were not to be challenged, the New Testament prophet submits his revelations to the congregation who are directed to evaluate them in light of the scriptures and the testimony of the Spirit. The church, not the prophet, is the arbiter of epiphany. And although in very specific situations he might foretell events, the prophet’s primary role as part of the New Testament church is not to predict the future or enforce mandates but to provide timely insight and impetus.

The great and ongoing prophetic task is to express the inexpressible. The prophet must attempt to articulate an immanent transcendence that he himself cannot fully comprehend. The infinite must contract into a span. The mountain must become a molehill. The Word must become words. The prophet condenses the ethereal vapors of divinity into the cracked jars of language; he is a distiller of Spirit.

A common misconception about the biblical prophet is that he is a passive recipient, that God downloads the message verbatim into the prophet’s awareness, and the prophet, in turn, records the words as delivered. This is how the devotees of the Koran believe their book came about. The biblical prophets did indeed often relay the very words of God as they received them. Thus saith the Lord signals that what follows is exactly what God has uttered, without interpretation or explanation. However, a great deal of the Bible’s prophetic literature is not a matter of mere dictation. Large swaths of Old Testament revelation and nearly all in the New Testament epistles involve heavenly visions and prophetic impressions that had to be rendered in human language. Prophecy is rarely an exact science; there is an art to the oracle.

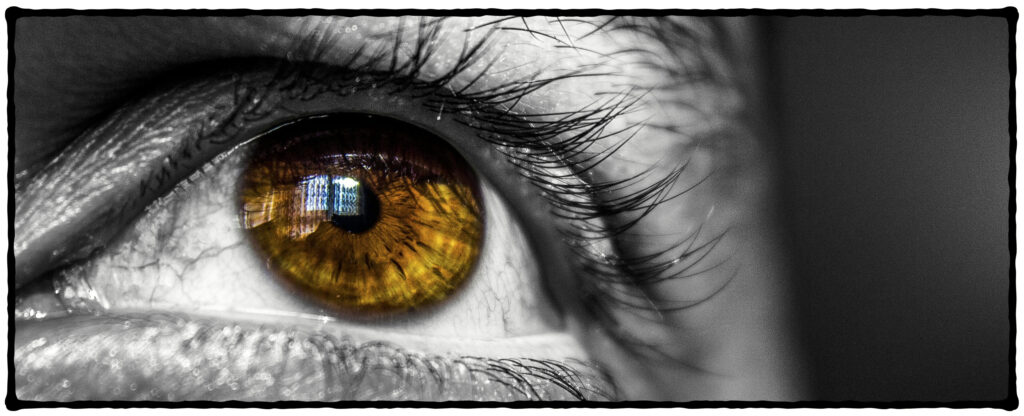

The prophet’s primary asset is the gift of special sight. He has the ability to see things that the rest of us do not; he is a seer—or a see-er. Prophetic sight is not unlike that of any true artist. For example, what the rest of us would see as a simple, beautiful landscape, Vincent Van Gogh would see as a lusty explosion of color. Here is an except from a letter in which he describes a current project:

It is a view of flat green fields with haycocks . . . And on the horizon, in the middle of the painting, the sun sets in a fiery red glow. It was altogether a question of color and tone, the hues of a spectrum of colors of the sky: first, a violet haze in which the red sun was half-hidden by a dark purple cloud with a thin, brilliantly red border. Near the sun were reflections of vermillion but, above, a band of yellow that turned into green and, higher up, a shade of blue, the so-called “cerulean blue,” and, here and there, lilac and gray clouds catching the reflections of the sun.

This kind of sight cannot be learned; it is a gift. In the case of the prophet, God has granted him both the ability to perceive heavenly realities and the access to them. Ezekiel begins his book with the heavens were opened and I saw visions of God. 600 years later, John prefaces his astonishing Revelation similarly: After this I looked, and there before me was a door standing open in heaven. And the voice I had first heard speaking to me like a trumpet said, “Come up here, and I will show you what must take place after this.” The prophet has a special capacity to apprehend (if not always comprehend) the spiritual landscape, coupled with admission into it.

This does not mean that retrieving divine intelligence is easy. The prophet may be invited into the revelation zone, but fruitfully exploring it is another matter. Major exceptions notwithstanding, rarely is the prophet shown high-resolution images or handed a pre-printed scroll. More often he encounters a domain not so readily construed. I am not talking about some vacuous cloud of unknowing or dark night of the soul propounded by medieval mystics. On the contrary, the prophetic landscape gleams with light and revelation. The prophetic problem is not a lack of divine disclosure; it’s that there is too much. The prophet encounters a mind-blinding brilliance, a radiant roar of many waters that cannot be delineated because it is everything everywhere all at once. The first prophetic challenge is to recognize the particular disclosure. Peter alludes to the prophets who searched intently and with the greatest care, trying to find out the time and circumstances to which the Spirit of Christ in them was pointing when he predicted the sufferings of the Messiah and the glories that would follow. The prophet must pierce the incandescent murk in an attempt to discern the distinct “this/now” that he is seeking. If he is persistent and alert, the epiphany—or a part of it—will coalesce like a figure emerging from mist.

The second prophetic challenge is to articulate what is seen. The seer must condense the raw vapors of his experience into the liquor of human words. This is a difficult task, even for a master of language. Jesus himself grappled to render spiritual truth into words that by nature are imprecise. “What shall we say the kingdom of God is like?” he pondered, “or what parable shall we use to describe it?” His stories and sermons of “what he has seen and heard” are the finest things ever spoken among men, and yet they are fashioned with words that fall short of the very spiritual realities they are intended to convey. The apostle Paul, who, excepting Jesus himself, is arguably the church’s most articulate communicator, also recognized the unbridgeable chasm between human language and the heavenly realities to which they point: The kingdom of God is not a matter of words, he wrote, but of power. Even so, Jesus and Paul did use human language because in this dispensation there is no alternative. Miracles may validate the message, but they do not articulate it. For now, at least, words are necessary.

And so the prophet holds the vision in his mind’s eye, sharpens his pencil, pulls out his lexicon, and carries out his impossible mandate. He scratches, crosses out, ponders, revises, erases, and revises again. He loves the way words can be selected, honed, and linked to intimate the Spirit’s lucent visions. He also resents the words for failing him as he hammers their dull metal into a sorry semblance of epiphany’s exquisite contours. The Spirit will guide but rarely override; he is the Spirit of prophecy, not the prophet.

When the prophet has done his best, he will offer the fruits of his labor for consideration. He has no say in how it will be received. His expectations are modest. Some might understand and take his prophecy to heart; most won’t. But that’s not his problem; he is neither enforcer nor judge. The prophet’s job is to see and then communicate what he sees. He is an artist, a translator, a distiller of divinity. He is no more than that—and no less.