“You always resist the Holy Spirit.”

Acts 7:51

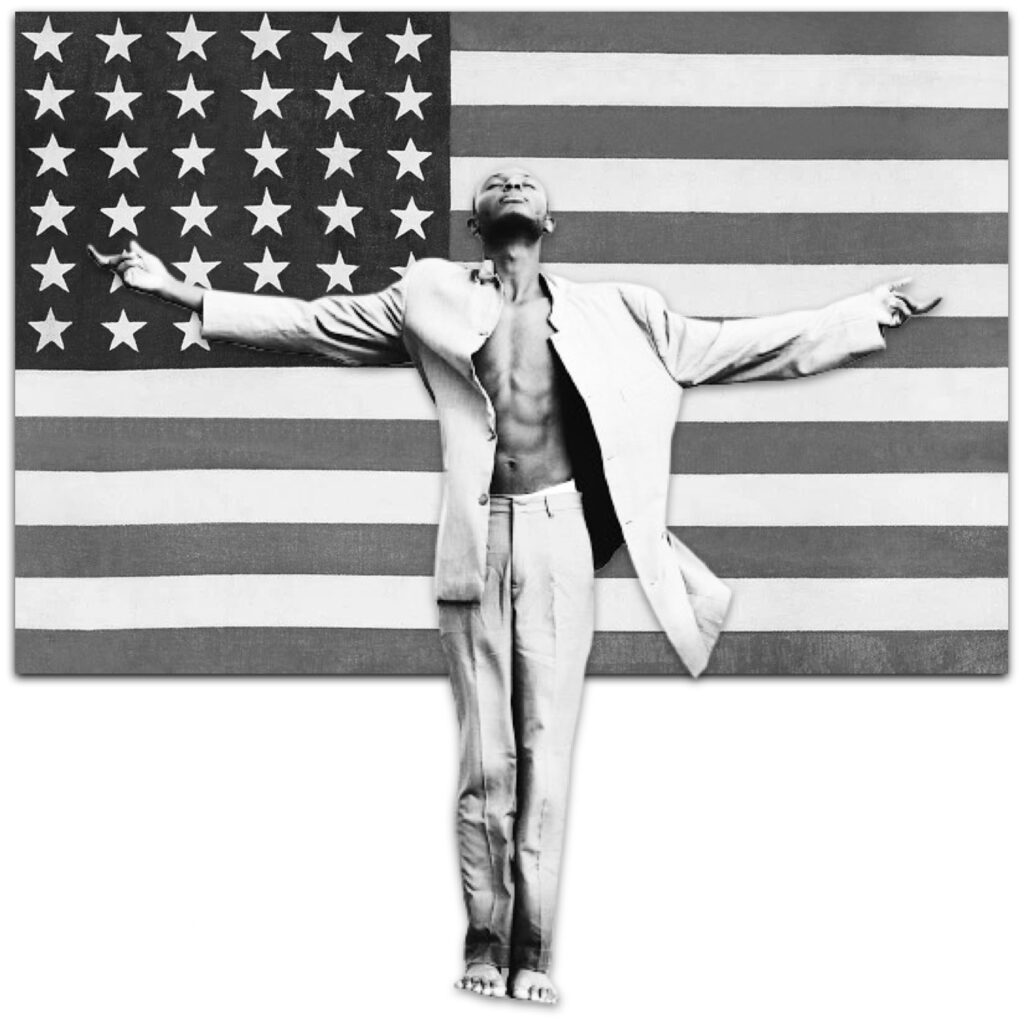

I am an American. My cultural DNA is native to this soil. I bleed red, white, and blue. I love big and bold. I am repulsed by monarchies. I am a son of the Declaration of Independence with an unassailable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If something doesn’t affirm me, I reject it utterly. If it gets in the way of self-actualization, I will discount it, disarm it, or destroy it. I will not surrender. Under my wrist beats the pulse of the free world. I am the measure of human potential, the template for triumph.

How can I be otherwise? God himself ordained it. It is he who appointed my time in history and the boundaries of my homeland. I do not apologize for what I am. I resonate with righteousness and will not be denied. My native prophets cry out in one accord. Trust thyself, proclaims Emerson. Believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men. We are our own masters. Self-reliance, he preaches, is the height and perfection of man. And Thoreau, our more grounded cousin, declares that what a man thinks of himself, that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate. I am my own means and destiny. My personal fulfillment is the whole point. Whatever satisfies the soul is truth, declares that most American of bards, Walt Whitman. I am the arbiter of my own certainties.

The American self is inviolable; it cannot be infringed upon by law or creed. Government, social practice, religion—all must approve and enhance the sacrosanct self. Here there is no authority but the self or those authorized to advance the self’s interest: of the people, by the people, for the people. The great American project is to subsume everything into the rubric of free and singular individual. For Americans, the White House, the Great White Way, and the little white church all raise the same anthem, whose lyric was penned by Whitman himself: I celebrate myself, and sing myself. The American anthem is a hymn of self-exaltation. Each American, whether religious or not, believes Emerson’s gospel: The currents of the Universal Being circulate through me. I am part or parcel of God. The American self is the alpha and omega, the beginning and the end.

This vein runs so deeply within us that American Christians do not recognize how profoundly un-American biblical Christianity actually is. The enemy of the glorified self is the wholly (holy) other. The holy shatters the illusion of a self-centric universe and obligates deference—which to the American self is a form of subjugation to be resisted.

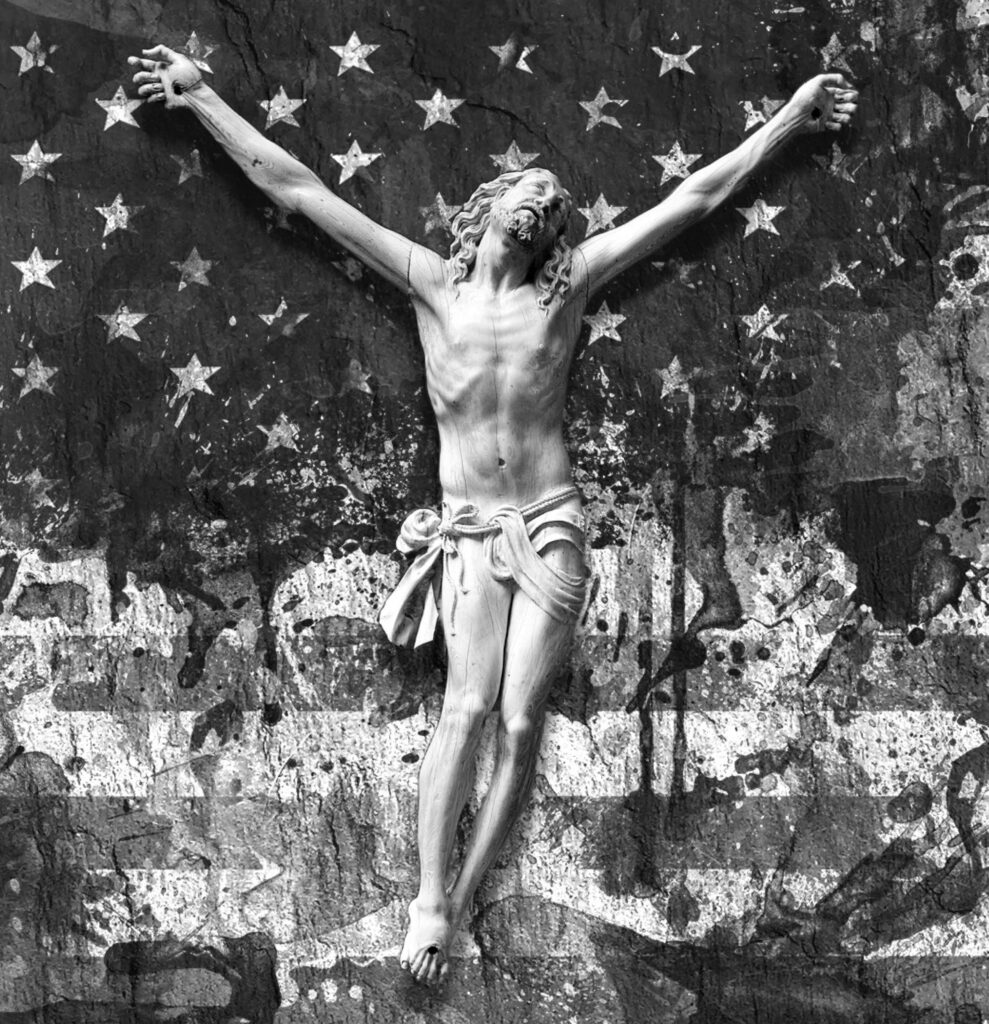

Ground zero is the Cross where the Absolute Other challenges all pretense of human—let alone American—self-reliance. Of course, American Christians cannot disavow the Cross; it is the very emblem of salvation. However, its devastating implications can be deflected by making the Cross only about Jesus. The American believer can then embrace the free gift of salvation and maintain the sovereignty of the self at the same time. The late Harold Bloom, a famous literary critic and keen observer of the cultural landscape (and an agnostic Jew) put it this way: Our sacred frenzies are directed towards ourselves or towards the resurrected Jesus; the American Religion takes up the cross only as an emblem of the Risen God, not of the crucified man, if indeed it takes up the cross at all. The American gospel is about saving the self, not losing it. Jesus died so that we don’t have to.

Jesus sees it differently. “If anyone would come after me,” he tells his disciples, “he must deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.” Jesus frames discipleship in the strongest possible terms. To follow him, he insists, means to renounce the self. “Whoever would save his life will lose it,” he explains. “But whoever loses his life for my sake will save it.” Christianity is not about the salvation or sanctification of the self; it is an utter repudiation of it. To be a Christian is to disown the self for the person of Christ. Paul is speaking quite literally when he declares: I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. The enshrined American self is the sworn enemy of the Cross.

If this were simply a matter of armchair theology, we might shelve it alongside other biblical curiosities—like the Trinity or the Nephilim or predestination—as mildly intriguing but without practical urgency. But the conflict between the sovereign self and the Sovereign Lord is no mere theological invention. The American Christian, whether conservative or charismatic, passive or passionate, is by nature and nurture diametrically opposed to the lordship of the crucified Christ.

And I am a quintessential example.

My reputation as a sincere and serious follower of Jesus is established. Like Apollos mentioned in Acts, I present as eloquent, fervent in spirit, and competent in the Scriptures. I have traveled around the world in service of the Kingdom of God and, for the past decade, have devoted myself to prayer. It is in the prayer closet where my resistance to the lordship of Christ is disturbingly apparent. As I am kneeling in prayer, I often become aware that am managing God. As I offer heartfelt praise or earnest petition, I am working quietly in the background to keep him within the invisible boundaries I have set for the encounter. Even amid the throes of rhapsodic worship, I find that I am maintaining against him a transparent but protective wall around my deepest self. My implied surrender isn’t surrender at all; it is a diplomatic assertion of terms: You may come this far but no further. Please maintain a safe distance. Even in the Holy of Holies the sovereignty of the self must be preserved.

And so I once more say amen and, having offered my reasonable service, rise, absolved and humming:

I’m proud to be an American

Where at least I know I’m free

But free from what? And at what cost?