Then the Lord relented and did not bring on his people the disaster he had threatened.

Exodus 32:14

When I was in second grade, I took judo lessons at the local YMCA. Once a week we donned our white judogis to practice flips and falls. I’ve never been much of a fighter, so I didn’t exactly enjoy the sport, but I did learn how to leverage my opponent’s weight and momentum against him and fling him to the mat. At recess one day, a big third-grader began to bully me to impress his gang. My smaller pack timidly stepped back to observe my humiliation. I have no idea how it happened, but as the thug came to shove me, I grabbed his arm, thrust out my hip, and slammed him to the dirt. The onlookers were as shocked as I was, but I looked down at my vanquished foe and said, in the levelest voice I could muster, “I know judo.” The third-graders never bothered me again.

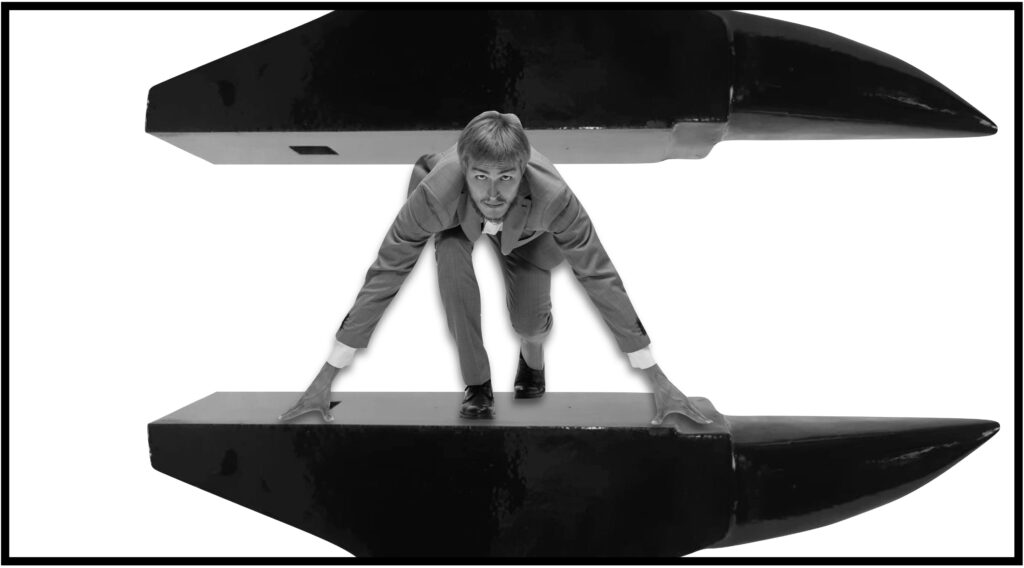

I don’t know if Jacob employed any martial arts when he wrestled the angel, but he held his own and was able to force a capitulation from the superior (and no doubt irritated) heavenly being. That’s one way it can go with God. Prayer can sometimes be a straight-up David and Goliath thing. The lowly human faces off against the Almighty with no more than a dance belt and a tube of Chapstick and attempts to muscle a concession out of him. God actually loves a good fight. He stands in the ring and calls out, “Is there anybody here who will go toe-to-toe with me?” The crazy thing is that sometimes a foolhardy human actually wins. For all his might and sweeping sovereignty, every so often God can be made to cry uncle.

Sometimes God just has to be told no. It’s not that he’s wrong; God is always right. As the psalmist writes, The Lord is righteous in all his ways. But sometimes he has to be reminded of what’s in his best interest. For example, while Moses is hanging out with God on Mount Sinai, Aaron and the gang at the bottom decide to forge a golden calf and party down. God is not happy. “I have seen these people,” he tells Moses. “They are a stiff-necked people. Now leave me alone so that my anger may burn against them and that I may destroy them. Then I will make you into a great nation.” Moses (probably mindful of what a pain having his own nation would be) replies, “Why should your anger burn against your people, whom you brought out of Egypt with great power and a mighty hand? Why should the Egyptians say, ‘It was with evil intent that he brought them out, to kill them in the mountains and to wipe them off the face of the earth’? Turn from your fierce anger; relent and do not bring disaster on your people.” God decides that Odd Moe has a point and calls off the massacre. Whether that ultimately turned out to be a good thing is still open to discussion. But that’s a different story.

King David also had to tell God to chill. In one of the weirdest of many weird accounts of the Old Testament, we are told that God incited David to take a census of Israel and Judah. (In the later Chronicles culpability is shifted over to Satan to avoid an awkward conflict of interest.) And so, against the counsel of his military chief, David counts the fighting men of his kingdom. This arouses God’s anger—go figure—and he offers David a multiple-choice punishment. David opts for three days of plague in the land, and God sends an angel to administrate the outbreak. After 70,000 innocent people have died, David finally appeals to the Lord. “I have sinned,” he points out. “These are but sheep. What have they done? Let your hand fall on me and my family.” David builds an altar on which he offers sacrifice, and the Lord pulls the plug on the plague. It appears that sometimes God can actually take no for an answer.

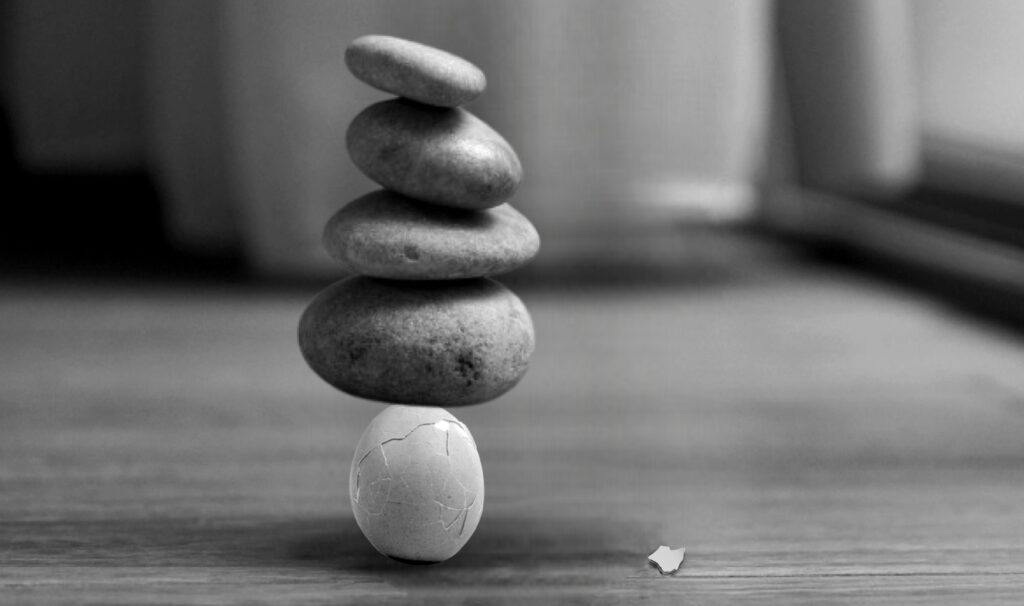

The Moses and David incidents point to the astonishing—and sobering—power that prayer has to alter the course of judgment. Divine justice rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked. It is, by definition, both impartial and inexorable. God neither punishes the innocent nor lets the guilty go free. The fact that God is just is fundamental to his character. As Paul writes to Timothy, he cannot disown himself. For him to withhold either reward from the righteous or punishment from the wicked would be unjust and would call into question God’s very nature and character. In other words, it is impossible for the true God to forgo the dictates born of his being.

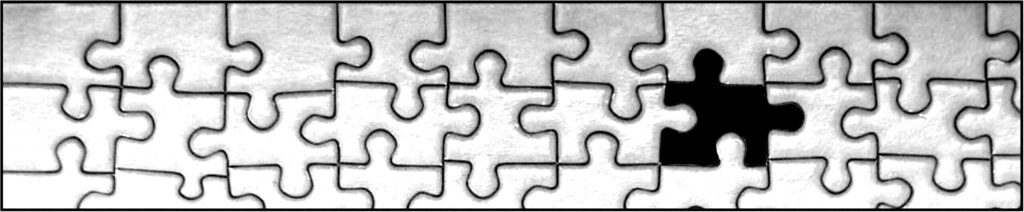

Which brings into sharp focus the blasphemous privilege and power of intercession. To the prophet Ezekiel God laments, “I looked for someone among them who would build up the wall and stand before me in the gap on behalf of the land so I would not have to destroy it, but I found no one.” This is one of the most poignant confessions in all of scripture; it reveals the unbearable problem of a God who is both just and loving. God is compelled by his infinite justice to destroy the land and its inhabitants, but he does not want to. He searches for someone who will stand between himself and himself, to advocate both for the land and argue against punishment. What is remarkable is that God himself seeks to be resisted. The tragedy is that resistance was not then to be found.

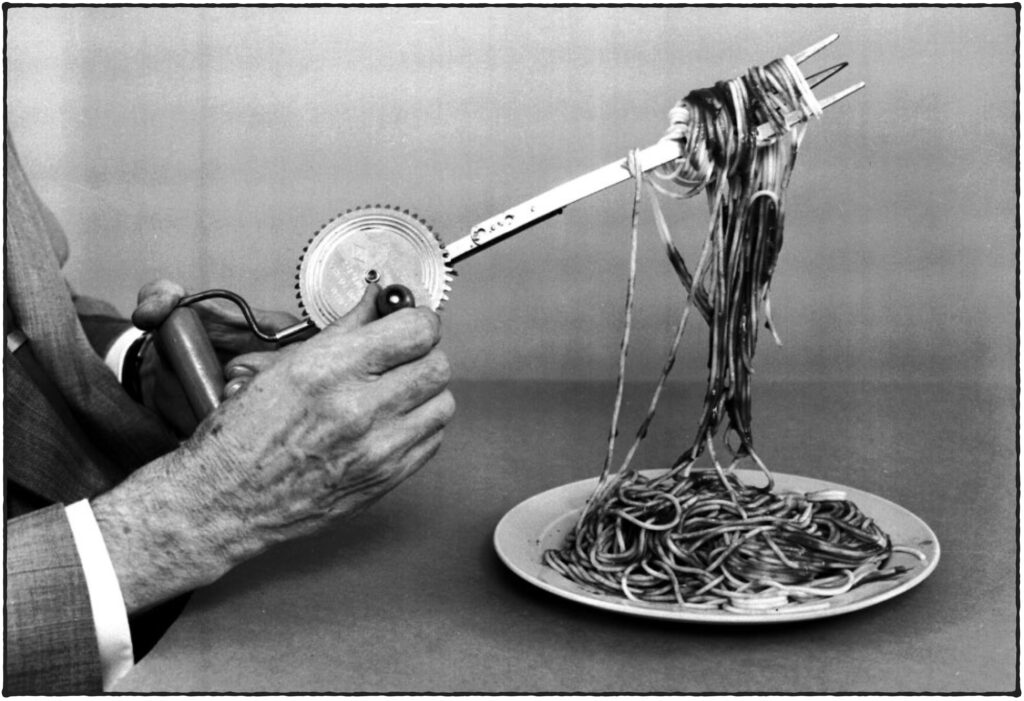

Of course, the perfect advocate did come, the Son who is sent into the world. As Isaiah declares, He saw that there was no one, he was appalled that there was no one to intervene; so his own arm achieved salvation for him, and his own righteousness sustained him. The Cross is the crux of God’s advocacy against himself. Jesus is the supreme mediator between a just God and humankind. But in Christ the saints are awarded the same audacious power to stay the hand of inexorable judgment. We, too, are awarded the privilege of altering the unalterable. God does not show favoritism, Paul asserts, but as James reminds us, the prayer of a righteous person is powerful and effective. Through prayer the saints can stand between divine intention and execution, challenge the sovereign God, and perhaps, just perhaps, change the course of destiny.

Engine against th’ Almighty, sinner’s tow’r,

Reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear

from “Prayer” by George Herbert