We want each of you to show this same diligence to the very end,

so that what you hope for may be fully realized.

Hebrews 6:11

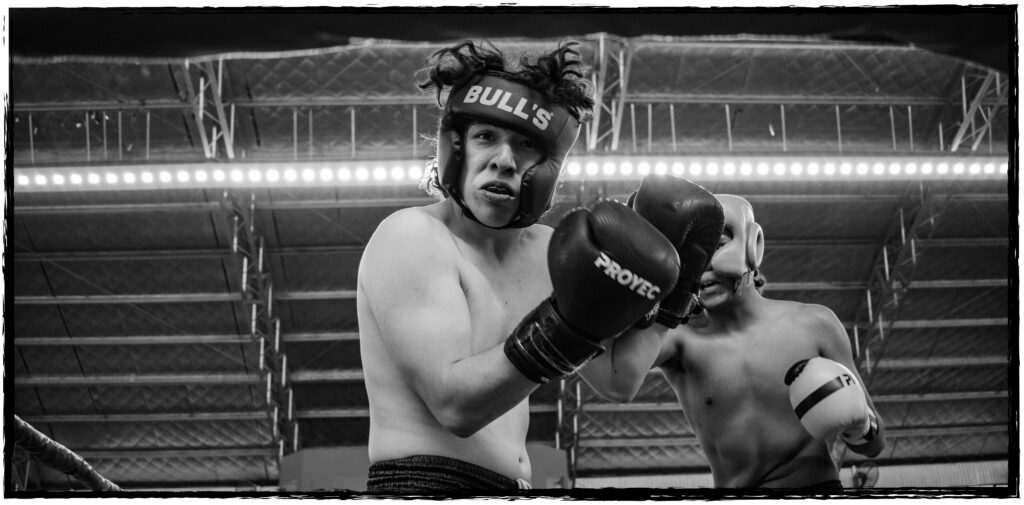

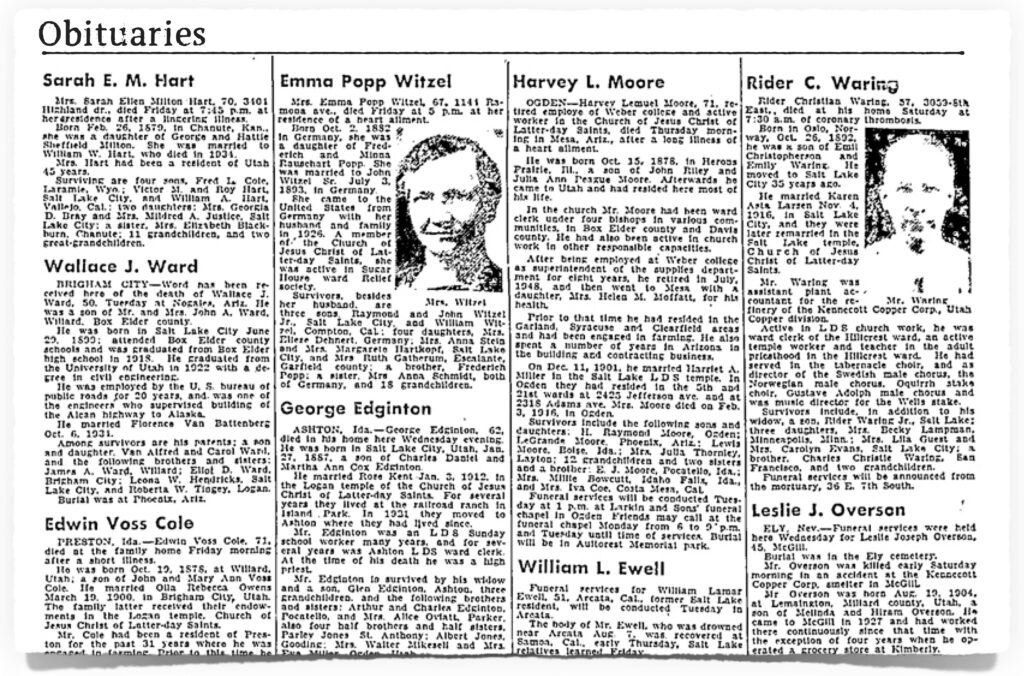

A story is told about an artist who was famous for his simple but exquisite sketches of roses. One day a man came into his studio and told the artist that he had long admired his work and would like to commission a sketch as a gift for his wife on their anniversary. The artist placed a fresh sheet of paper on his easel and, with a few confident gestures, rendered a beautiful image of a rose. The man was delighted. It was exactly what he had wanted. But when the artist informed him of the steep price, the man blanched. “That’s outrageous!” he cried. “It took you only moments to finish!” The artist sighed and led the man through a door into a large room. The walls were covered with thousands of sheets of paper. Upon the floor towered stacks upon stacks of canvases. On each sheet and canvas was a meticulously wrought sketch of a rose. “This,” said the artist quietly, “is where I have labored to perfect my art.” He gazed kindly at the astonished man. “The rose I created for you has taken me a lifetime.”

Stephen Curry is one of the best professional basketball players of all time. He lights up the court with his ball handling and shooting skills. Curry is a four-time NBA champion, a two-time NBA Most Valuable Player, an NBA Finals MVP, a two-time NBA All-Star Game MVP, and he’s the first player in NBA history with 4000 career 3-pointers. The apparent ease with which he razzle-dazzles fans and players alike is misleading. Curry practices hard. “I take hundreds of shots in a single workout,” he reveals. “It’s about muscle memory and consistency.” His ball handling drills include figure 8s, behind-the-back crosses, and one-hand behind-the-back movements up and down the court, over and over and over. On Mondays he works his chest (push-ups, nautilus presses). Tuesday is back day (pull-ups, seated rows). Wednesdays he focuses on his shoulders (Arnold presses, lateral raises). On Thursdays he works his arms (bicep curls, tricep press-downs). His practice sessions run anywhere from 90 minutes to three hours, day after day. What the fans see is a game-time superstar putting on a show.

That’s the way of it. Whether it’s success in the arts, in sports, in business, or even in the kitchen, most of us see only the finished product. We wonder at a Michelangelo, cheer a Muhammad Ali, admire a Steve Jobs, or rave about Mom’s apple pie. What we do not see, however, are the hours or days or years that it took to make it happen. It is true that many who are at the top of their various fields have special gifts. No matter how hard we might try, we will probably never out-Mozart Mozart. Even so, rarely is the gift alone enough. (The road to success is littered with the failed husks of the gifted.) As the parable of the talents teaches us, the wise know that they must invest their gifts if they hope for a return. There is no guarantee that the investment will bring the desired results—Stephen Curry does have a bad game from time to time— but disappointment is indeed certain if the gifted do not put their gifts to work. Without guts there is no glory.

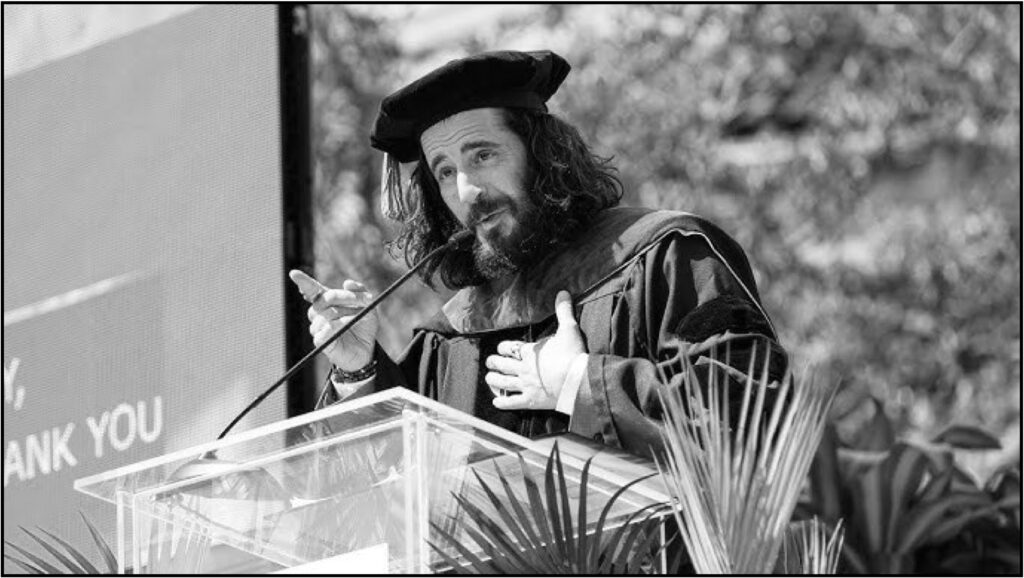

For over 25 years I have headed up a small nonprofit organization called Burning Bush Ministries. Whenever I am asked what it is we do, I usually reply that our primary role is teaching church leaders but that we also support Christian missionaries and aid community development around the world. This answer usually suffices. If they are interested, I can relate tales of dramatic visitations of God or unnerving manifestations of evil. I can show photos of me preaching in India and Africa and Brazil or wading through monsoons in Bangladesh or trudging through the Russian snow. These are the exploits that we showcase in our newsletters, emails, and campaigns, the highlight reels that I hope will justify my vocation.

Every so often, though, a curious someone presses further and asks what I actually do during a typical day. I hate that question. It’s not that I don’t know the answer; it’s that I’m actually kind of embarrassed by it, mostly because, for many people, it would appear that I don’t do much of anything. And so before I answer, I consider who is doing the asking. If it is an unbeliever, I will say that each morning I have a meeting with the CEO of my organization. That meeting, I tell them, may last an hour, the morning, or even the whole day. After that I will attend to the projects at hand, whether it is studying, writing, or planning. They tend to nod with understanding, and I’m generally off the hook.

But if the curious questioner happens to be a passionate follower of Jesus, one who is acquainted with the dynamics of the heavenly realms and the alien mechanics of the Kingdom of God, if I deem that person a kindred spirit and faithful servant of our common Lord, I may tell him the undisguised truth: what I do is pray. For over a decade prayer has been my primary daily activity. It is ground zero for everything else I do. When I am in prayer I am at the center of all things and all times. In prayer I reach across oceans, lift up the weary, bring down the proud, demolish lies and pretensions, hold back the tide of wickedness, and establish sanctuaries of grace and peace. In prayer I carry my brother’s burden, believe for him when he cannot, and clear a path for his steps. In prayer I take up the great cause of righteousness. I cry out for mercy, for justice, and for truth. In prayer I am advocate, ambassador, and avenging angel.

The real work happens there, in the trenches. All else is razzle-dazzle.