“When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams — this may be madness. Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!”

Cervantes, Don Quixote

If we have lost our minds, it is for God.

2 Corinthians 5:13

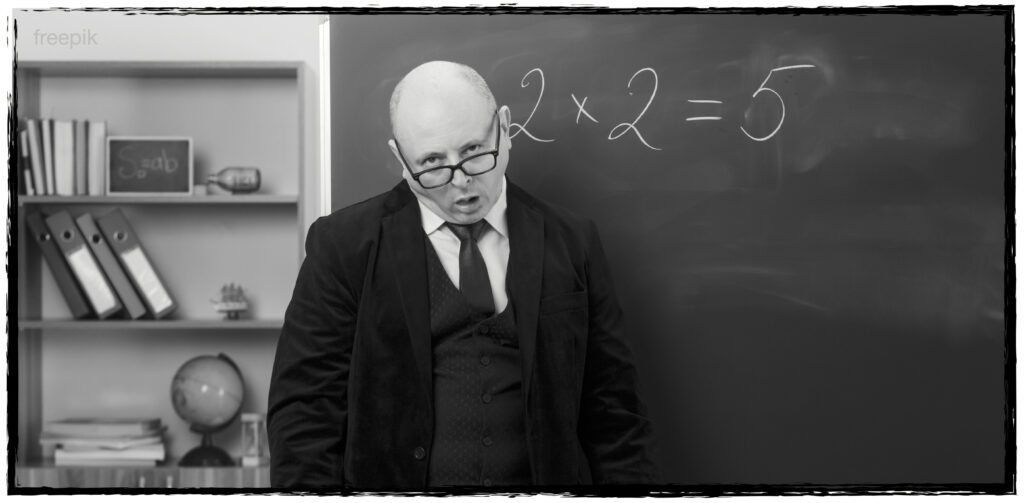

The gospel is crazy talk. We have forgotten that. Subjected to centuries of erudite insistence that the church’s message is fundamentally rational, we have grown desensitized to the outright lunacy of our claims.

When we say that a person is rational, we mean that he possesses normal or sound powers of mind. This is the quality that Jesus restored to the man whom he delivered from the demonic Legion. Both Mark and Luke report that the man regained his right mind; he is once again a rational human being. When we say that some thing is rational, we mean that it aligns with the way things actually are, including with how our minds work; in other words, the thing makes sense.

The list of those defending the essential rationality of the gospel is a Who’s Who of Christian thought: Thomas Aquinas, Jonathan Edwards, John Calvin, G.K. Chesterton, R.C. Sproul, and the 20th century’s reigning champion, C.S. Lewis, to name but a few. In general, and with each allowing for miracles (those inescapable, embarrassing anomalies), they argue that the Christian belief system is founded on rational assertions and is logically coherent. Virtually every sermon I have ever heard presumes the rational intelligibility of the Christian message. We are convinced that the gospel is explainable.

However, in spite of the many intellectual heavyweights who have argued that Christianity is a rational faith, the New Testament writers are not so obliging. The gospel may indeed be the power of God to those who are being saved, but it’s not only the unbeliever who finds the church’s message foolishness. The god-smacked Paul himself admits to the folly of what we preach. As much as we might like it otherwise, the New Testament proclamation is neither rational nor reasonable nor relevant. There’s no way around it; the gospel of Jesus Christ is insanity on a stick.

Rational?

The biggest obstacle to a rational Christianity is Christ himself. If it weren’t for Jesus, X-ianity would parse just fine. But how do you solve a problem like Messiah? The gospel’s central assertion is that in Jesus, as Paul puts it, all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form. This poses an insurmountable issue for anybody who hopes to formulate a rational system of belief. Even Jesus can’t seem to get his theology straight. On one hand, he asserts that “God is spirit.” On the other, the risen Jesus shows himself to his disciples and reassures them that “a spirit does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have.” On one hand, John insists that no one has ever seen God. On the other, Jesus declares, “Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father.” This schizoid dance finds its culmination in Paul’s most succinct statement about the nature of Jesus Christ:

He is the image of the invisible God.

It doesn’t take a theological Einstein to note that this statement is pure nonsense. If something has an image, it’s not invisible; if it’s invisible, it doesn’t have an image. How is it possible to build a rational system on top of that? We have certainly tried. But as Oliver Wendell Holmes noted, insanity is often the logic of an accurate mind overtasked.

The wicket is so sticky that the late John Wimber, a professor at Fuller Theological Seminary and influential founder of the Vineyard movement, felt the need to coin a new word—transrational—to classify the gospel’s disregard for reason. But it is Festus, the Roman governor who listened to Paul’s gospel presentation, who tells it like it is. In the middle of Paul’s defense, Festus interrupts him and shouts, “You are out of your mind, Paul! Your great learning is driving you insane!” The governor has a point. There is nothing sensible about the gospel of Jesus Christ. It may be true, but it is decidedly not rational.

Reasonable?

For most, or for most Christians anyway, the absurdity of the gospel’s central claim is only a mild curiosity, a benign theological oddity of little, if any, practical concern. Far more problematic are the gospel’s demands, which Jesus summed up in a single devastating ultimatum:

“Anyone who does not renounce all that he has cannot be my disciple.”

This isn’t a one-off either. Jesus tells the rich young ruler who had come to him seeking eternal life, “One thing you lack. Sell all that you have . . . and come, follow me.” At many times and in many different ways, Jesus insists that those who wish to follow him must give up everything and take up the cross. The Twelve accept this at face value. Peter confesses to Jesus, “We have left everything and followed you.” For the first disciples the gospel of Jesus was an all or nothing proposition.

This is untenable for today’s Western Christians. To renounce all we have as a condition of discipleship reeks of fanaticism. Except for the mythical saint or religious whacko, to give up everything to follow Jesus is not only unreasonable but realistically impossible. No one in his right mind could entertain Christ’s demand literally.

So we don’t. Our preachers and commentators help us finesse away the brute force of Christ’s words and to shape a less literal, more amiable mandate. A sampling:

- It’s not a physical giving up but a mental and emotional letting go.

- Being a disciple of Jesus Christ requires us to let go of our own desires, interests, and priorities.

- This passage speaks to the importance of loyalty and allegiance to Jesus over all other competing loyalties, including family, self-interest, and possessions.

- This figurative passage means to let nothing stand between us and Jesus.

An unmitigated Jesus is not reasonable. His gospel is extreme, disruptive, and unworkable in the modern age. Apparently, he hadn’t foreseen that.

Relevant?

One of the hallmarks of the reasonable gospel is the promise of a better life. The sensible church is in the personal enrichment business and offers a Jesus whose main job is to make life better, as is evidenced by the standard issue sinner’s prayer which instructs us to “ask Jesus into our lives.” But according to Jesus and the New Testament writers, we have no life to ask Jesus into; humanity is as dead as a doornail. The kingdom of God is not relevant to the world; it has nothing to do with the kingdom of this world at all. Paul declares:

What do righteousness and wickedness have in common?

Or what fellowship can light have with darkness?

The answer is nothing. Absolutely nothing. The gospel does not enhance anything. Jesus did not come to improve the world’s system but to extract people from it. “My kingdom,” Jesus explains,“is not of this world.” C.S. Lewis refutes any balderdash that Christ’s teachings would make the world a better place: Let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to. The gospel of Jesus Christ is not a fix for the world’s problems; it’s the portal to another reality altogether. To market Jesus and his message as relevant is to miss the whole point.

Jesus said, “I praise you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth,

because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned,

and revealed them to little children.”

Crazy Cats

Groucho Marx famously quipped, I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept me as a member. The church might wish to take heed. The more we attempt to package Christianity as rational, reasonable, and relevant, the harder is the sell. A gospel sanctioned by human reason, propriety, and priority is no gospel at all. It is mere religion. Who wants that?

The Word made flesh defies understanding. The Holy Spirit repudiates logical suppositions. The church’s message is utterly preposterous. John Milton’s epic attempt to justify the ways of God to man was doomed from the start. The gospel cannot be explained, but it saves all who believe.

And we who believe are also inexplicable. We are insanity incarnate, the new images of the invisible God. We are impossible, and yet here we are.

For since in the wisdom of God the world through its wisdom did not know him, God was pleased through the foolishness of what was preached to save those who believe.