Get back, get back, get back to where you once belonged.

The Beatles

One of the late comedian George Carlin’s most famous routines, A Place to Put My Stuff, playfully exposes our tendency to accumulate things. It’s a brilliant set piece that showcases Carlin’s razor-sharp observation and his masterful use of language. According to Carlin, we never seem to have enough space to store our stuff. (To see a sanctified excerpt of his routine, click here. For an unbleeped version click here.) Stuff R Us.

Nowhere is Carlin’s comedic insight more apparent than with the self-storage business. Over the past 40 years, the self-storage industry has been one of the fastest growing sectors of the U.S. commercial real estate industry. There are approximately 52,300 storage facilities in the U.S. To put that into perspective, there are as many storage facilities as there are American locations of Starbucks, McDonald’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, Pizza Hut and Wendy’s combined. Self-storage facilities contain an average of 546 units each, and even though that amounts to one unit for every 12 Americans, the industry boasts a 96.5 percent average occupancy rate. Most surprising—or maybe not—is that over three-quarters of self-storage tenants are homeowners, and 65 percent of all self-storage renters have a garage. Apparently, the bigger the place, the smaller the space.

Every so often I discover that I, too, am overrun by clutter. I don’t mean by material things, though my own garage might suggest otherwise. What I mean is that I find myself beset by invisible flotsam that has slowly accumulated around my soul. It’s hard to characterize these stealthy accretions; they are as hazy and ethereal as smoke. Attempting an inventory is futile. Besides, it’s only taken altogether that these blurry barnacles register at all.

For me, the tell-tale sign of soul clutter is an inner fuzziness. When I’m running lean and mean, I blaze with clarity, as though my spirit surges with an astringent hit of pure being. I’m a clear channel for high voltage reality. When I’m cluttered, I feel like a sluggish, debris-clogged backwater.

Of course, attempting a detritus dump in order to recover some vaguely imagined authentic self is about as productive as emptying the trash on the Titanic; and if it came down to it, I’d rather bunk on a crowded cargo ship that at least gets me where I want getting to. The ark may not be fancy, but it floats. Decluttering the soul is not metaphysical tidying up.

The only remedy that I’ve found for soul clutter is a wholesale reset. There’s no going through the pile to see what’s worth keeping; all of it’s the problem. And since attempting to off-load intangibles is a fruitless endeavor anyway, the one solution is to abandon ship and start at the very beginning—which, I’ve heard, is a very good place to start.

And this is where the impractical demand of the gospel may actually be [gasp] a practical godsend. Jesus sets down impossible terms for would-be disciples: “Any of you who does not give up everything he has cannot be my disciple.” Seriously? Give up everything? How in hell (or heaven or earth) is a chronic hoarder supposed to pull that off? What does give up everything even mean? But there it is like the thorn of a rose, inescapable and nonnegotiable. First practical insight: In spite of all the precious crap you’ve amassed, in both house and heart, the reality is that you’ve got nothing to lose. You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. (I said practical not agreeable.) You’re bankrupt; you might as well declare it.

But although most of us know—as do an unfiltered Carlin and Apostle Paul—that our stuff is shit [σκύβαλον, Philippians 3:8] we’re still loathe to part with it. It may be shit, but it’s essential shit, and we want to hang onto it. And so we revise the terms of endearment so that we can have our Christ and keep shit too.

If it were merely a matter of divine edict, we might be able to get away with it by pleading our humanity and playing the grace card. But we’re not dealing with an aloof divinity who lays down the law from on high. We’re dealing with a carpenter who had the audacity to actually practice what he preached. This Jesus, claims Paul, who was in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but emptied himself. This is extraordinary and terrifying, so terrifying, in fact, that many commentators simply cannot accept Paul’s claim at face value. His Greek, however, is crystal clear: To take on the nature of humanity, Jesus completely drained himself of whatever it meant for him to be in the form of God. Deal with it. Second practical insight: Decluttering the soul isn’t about off-loading the stuff; it’s about off-loading the self—and the self cannot off-load itself.

There’s only one place you can go for that, only one place where you can lay down both your soul and your inability to lay it down. I’d tell you, but you’re not desperate enough. Besides, you already know where. But you like the clutter—or if not exactly like it, you definitely want it more than you don’t. I know this. So do you. The only thing empty is your protest.

So what are you forfeiting? You have no idea. You literally have no idea. Beyond this point everything is for you only words, just more stuff to add to the pile. (Let’s call this pile the earnest Christian pile.) This is why you are what you are. I know this too.

And this is why we are what we are instead of what we could be.

Could I, if offered glistening wings,

break free, or would I clutch, afraid,

the turning leaf, this hull I’ve made,

this chrysalis crafted from my things?

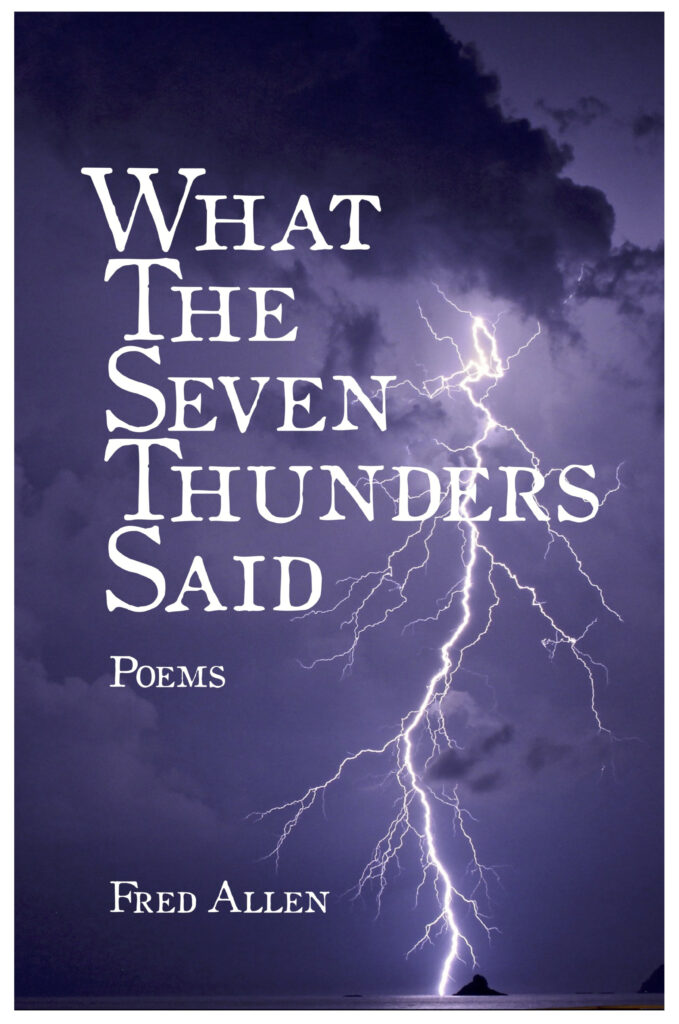

Newly Published

In John’s astonishing and enigmatic Revelation, he overhears the voices of the mysterious Seven Thunders, but he is commanded to seal up what they say and not to write it down. Allen too has heard their voices, and in a series of oracles, notably concise and immediate, he unseals their urgent testimonies. This collection showcases the unique power of poetry to embody elusive spiritual realities in all their Delphic glory.

Available now exclusively at Lulu. Order here.